Hepatitis

You may also want to view the ECI acute liver failure and chronic liver failure tools.

Hepatitis, a general term referring to inflammation of the liver that may result from various causes, both infectious (e.g. viral, bacterial, fungal, parasitic) and non-infectious (e.g. alcohol, drugs, autoimmune and metabolic diseases). Viruses are the most common cause with 1 in 12 people having viral hepatitis worldwide. There are 6 different types (A-G). In Australia the most common are hepatitis A, B and C.

These 3 viruses can all result in acute disease with symptoms of nausea, abdominal pain, fatigue, malaise, and jaundice. Very high aminotransferase values (>1000 U/L) and hyperbilirubinemia are often observed. Severe cases of acute hepatitis may progress rapidly to acute liver failure. Hepatitis B and C can lead to chronic infection and may go on to develop cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) is defined as acute liver failure that is complicated by hepatic encephalopathy. FHF may occur in as many as 1% of cases of acute hepatitis due to hepatitis A or B. Whether hepatitis C is a cause remains controversial. More than half of all cases result in death unless liver transplantation is performed in time.

Any patient with suspected hepatitis requiring admission to hospital should be isolated and have infection control and contact precautions in place until the diagnosis is confirmed / excluded.

Hepatitis A

- Usually mild, self-limiting illness. Rarely develops into Fulminant Hepatic Failure (FHF).

- Spread by faecal-oral route. Often after investing infected food or water; handling infected linen or nappies; or by direct contact (including sexual).

- Incubation period 15-50 days, average of 30 days. Virus is excreted for up to 2 weeks before onset of symptoms.

- Symptoms include - Anorexia, lethargy, jaundice, weakness, vomiting and fever, followed by dard urine, jaundice and pale stools. Investigations reveal elevated bilirubin and AST/ALT +/- cholestatic hepatitis with elevated ALP, rarely FHF.

- Can be asymptomatic especially in children.

- Most people feel better and LFTs begin to normalise a month after onset of illness. HAV does not become chronic.

- Overall mortality is approximately 0.01%; severity of symptoms and mortality increase with age.

- Detection of IgM hepatitis A antibodies (anti-HAV IgM) confirms recent infection. These antibodies are present for 3-6 months after infection. Detection of IgG hepatitis A antibodies (anti-HAV IgG) indicates past infection and lifelong immunity against hepatitis A infection.

- Treatment is supportive.

- Vaccine available to prevent HAV, for example, travellers to endemic areas. Protection begins within 14-21 days after the first dose. A second dose of vaccine is required for long-term protection. The duration of immunity following vaccination is not certain, however, it appears to be at least 10 years, probably longer.

- Patient education - Inform food handlers suspected of having HAV that they should not return to work until their primary care physician can confirm that they are no longer shedding virus. Instruct patients to refrain from using any hepatotoxins, including ethanol and acetaminophen.

- Hepatitis A is a notifiable disease to the Public Health Unit on 1300 066 055.

Hepatitis B

- Most common liver infection in the world - 257 million people worldwide infected and more than 800,000 people die every year due to consequences of HBV (WHO).

- Prevalence highest in Western Pacific and African Regions at 6.2% and 6.1% respectively, most becoming infected with HBV perinatally or during early childhood (WHO).

- Transmitted parentally, sexually or perinatally from mother to infant – high risk groups include Indigenous Australians, high risk sexual activity and people who inject drugs. In Australia, it is estimated that 232,000 people are chronically infected with hepatitis B. However, one-third of those living with chronic hepatitis B in Australia are undiagnosed (WHO).

- The Hepatitis B Virus can survive out of the body for more than 7 days during which time it can infect someone who is not taking adequate precautions or not vaccinated. The incubation period is 30-180 days, average 75 days.

- Clinical illness associated with acute HBV infection ranges from mild disease to Fulminant Liver Failure (FHF).

- Infants and children rarely experience symptoms of acute infection.

- Symptoms include anorexia, nausea/vomiting, lethargy, abdominal pain, myalgia, jaundice or dark urine.

- 95% of adult patients and 5-10% infants ultimately clear the virus without treatment and develop antibodies against hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and lifelong immunity to reinfection.

- About 5% of adult patients and 90-95% of infected infants are unable to clear HBV and develop chronic infection, causing liver scarring (cirrhosis). These people remain infectious.

- Chronic HBV patients have significantly increased risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC).

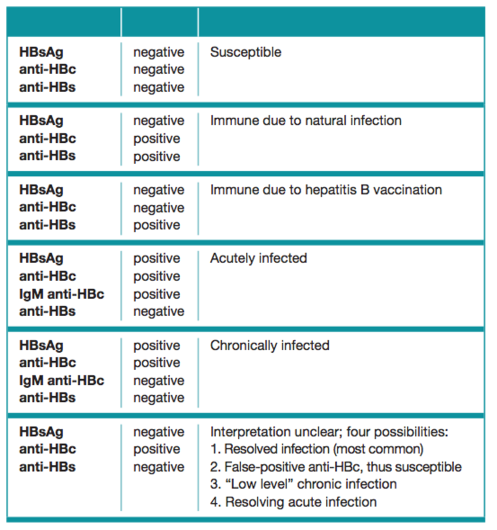

- Blood markers table (see below).

Table: Interpretation of Hepatitis B Serologic Test Results, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention

- Treatment - chronic infection with normal LFTs do not require treatment but 6 monthly monitoring. Those who have deranged LFT may be started on various antiviral drugs such as tenofovir or entecavir as per liver specialist.

- People who have been exposed and not been vaccinated should receive hepatitis B immunoglobulin within 72 hours and a hepatitis B vaccination as soon as possible/within 7 days of exposure.

- Patient education - Refer patients with infectious hepatitis to their primary care providers for further counseling specific to their disease. Counsel patients regarding the importance of follow-up care to monitor for evidence of disease progression or development of complications.

- Hepatitis B is a notifiable disease to the Public Health Unit 1300 066 055.

Hepatitis C

- Estimated 71 million people have chronic HCV worldwide, and more than 230,000 in Australia (WHO).

- Transmitted parenterally, perinatally, and sexually. In Australia most newly diagnosed patients nowadays caused by unsafe IV drug use.

- There is no vaccine available.

- HCV has a viral incubation period of approximately 8 weeks (ranging between 2 weeks and 6 months). Most cases of acute HCV infection are asymptomatic. Even when it is symptomatic, acute HCV infection tends to follow a mild course.

- Approximately 15-30% of patients acutely infected with HCV lose virologic markers for HCV, ie 70-85% may develop chronic liver disease.

- In chronic hepatitis, patients may or may not be symptomatic, with fatigue being the predominant reported symptom. Aminotransferase levels may range from

- Approx 20% of patients with chronic HCV experience progression to cirrhosis. This may take 10-40 years.

- Patients with HCV - induced cirrhosis are also at increased risk for the development of HCC, especially in the setting of prolonged duration of infection, HIV or HBV coinfection, male gender, associated alcohol abuse.

- Treatment is dependent on the genotype of the HCV. Genotype 1 and 3 are predominant in Australia. Newer direct-acting antivirals (e.g. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir) are well tolerated, daily-dosed medications taken for 3-6 months and can achieve cure rates of more than 95%. Unfortunately, less than 2% of those infected with chronic HCV in Australia seek and receive treatment.

- Patient education - Refer patients with infectious hepatitis to their primary care providers for further counselling specific to their disease. Counsel patients regarding the importance of follow-up care to monitor for evidence of disease progression or development of complications.

Hepatitis D

- HDV requires co-infection with HBV.

- Worldwide the pattern of HDV is similar to the occurrence of HBV infection and it has been estimated that 5% of those living with chronic HBV (~15 million people) are infected with HDV. It is not common in Australia.

- Overall, numbers of people with HDV has decreased since the 1980s due to successful HBV vaccination programs.

- Spread parentally and sexually.

- Simultaneous acute co-infection with both HBV and HDV may result in severe or fulminant hepatitis, although 95% of cases will recover spontaneously and clear both viruses.

- HDV superinfection of an HBsAg positive patient—90% of these cases develop chronic HDV. Chronic HDV results in accelerated progression to cirrhosis and liver failure, and an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

- No specific treatment for HDV i.e. treatment used for HBV has no benefit.

- Co-infection with HDV can be prevented through hepatitis B vaccination.

- There is no medication or vaccine to prevent HDV superinfection in people with chronic HBV. Prevention of HDV superinfection can only be achieved through education to reduce exposure to infectious blood.

- HDV is a notifiable disease.

Hepatitis E

- HEV is not common in Australia. Most cases are acquired overseas.

- Transmitted via faecal-oral route and highest rates of HEV infection occur in regions where there is poor sanitation and sewage management that promotes the transmission of the virus. HEV can also be transmitted vertically to the babies of HEV-infected mothers. It is associated with a high neonatal mortality.

- HEV causes an acute illness but rarely causes a chronic infection.

- The time between infection and development of symptoms ranges from 15-60 days, average 40 days (WHO, 2005).

- Symptoms of acute HEV are similar to those of other types of viral hepatitis – fever, fatigue, anorexia, nausea/vomiting, jaundice, fluctuating aminotransferases.

- In general, people recover with no long lasting illness. 1–4% develop FHF. Pregnant women who become infected with HEV are at greater risk of severe illness and liver failure and 20% may die because of the infection. However, this occurs mainly in developing countries where HEV is very common and where there is limited healthcare for pregnant women.

- Diagnosis of HEV is performed by a blood test that detects either the antibodies or the virus itself. The blood tests needed to diagnose HEV are not widely available.

- Treatment is supportive.

- Prevention is the most effective approach against HEV.

- No vaccine exists for the prevention of HEV, provision of clean drinking water and good personal hygiene education are mainstay.

- HEV is a notifiable illness.

Further References and Resources

Buggs, A. et al. (2014) Viral Hepatitis, Medscape.

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention - Hepatitis.

MacLachlan, J. H., et al. (2013) The burden of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Australia, 2011, Australia and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 2013, vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 416-422.

World Health Organization - Hepatitis.

Patient Fact sheets